I was in The Hague for a meeting of the Association of Defense Counsel at the International Courts (ADC-ICT). This was my last day in The Netherlands before heading home and it was snowing.

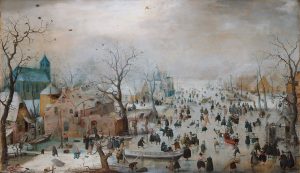

With images of Hendrick Avercamp’s impish 17th century paintings and childhood memories of Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates (book and movie) dancing in my head, I set out for the “centrum” to fill the last afternoon of my vacation. However, that snowy, frozen canal climate is long gone from this country. Unused to so much snow in a short period of time the Dutch city was, if not paralyzed, substantially slowed down.

After wandering around mostly deserted streets, I headed for the oh-so-convenient bus whose route dropped me practically at the door of the home of my friend Michael Karnavas, where I was staying. Over the next hour, it finally dawned on me that despite the illuminated boards assuring that the bus was 9 minutes, then 4 minutes, then 1 minute away, before disappearing from the board altogether, the buses had ceased running. So, I caught the tram to the beach, which I knew stopped behind the building housing the United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) a 10 minute walk from my lodgings.

As I walked back, I stopped by the Churchillplein fountain, in front of the Tribunal, to reminisce and contemplate its impending closing.

Much has been said and written about the legacy of the ICTY as it prepared to end its run at the close of 2017, not the least of which have been the waves of self-praise and a carefully choreographed farewell tour. As an observer since 2004, with an 18 month stint as counsel for an accused in 2006-2007, I have my own less praising opinions of the ICTY’s legacy:

- I believe the stubborn refusal to meaningfully revisit and refine or reverse some of its early jurisprudence has left a legacy with dubious legal precedent.

- I believe the ceaseless, shameless, publicity seeking actions of tribunal leadership, including Tribunal presidents who sit as appeals judges, in promoting prosecution in the former Yugoslavia, defining historical truth and participating in commemorative events, taints claims of fairness and impartiality. Not to mention the untold millions spent on these unseemly public relations activities.

- I believe the excessive attention to confidentiality, leading to mountains of confidential or redacted filings and decisions, not to mention all too often closed proceedings, undercut claims to transparent justice and undermined the credibility of the ICTY.

- I believe the inequitable allocation of resources, personnel and time to the defense of these cases needlessly undermined confidence in the system and denied many accused due process.

- I believe the failure to control the scope of the prosecutions led to trials that were too long and so unmanageable as to be incapable of rendering justice. Just look at Prlic et al. (IT-04-74) — nearly a decade and a half from indictment to appeal judgment.

- I believe the over-selection of judges with experience confined to academia or the diplomatic corps – without trial experience as either a judge or a lawyer – has led to uneven trials and impractical decision-making.

- Finally, I believe the structure of the institution, with the prosecutor inside the tent, has exacerbated both the perception and the reality of the ICTY as an institution more concerned with convictions and finding so-called historical truths, than with insuring fair trials and protecting the rights of the accused individuals.

Perhaps I am being too harsh. After all, as the first international criminal tribunal since the post-World War II Nuremberg and Tokyo International Military Tribunals, there was a lot of new ground to be trod. But the ICTY has already missed no opportunity to trumpet its own accomplishments, large, small or imagined. While I, to paraphrase Shakespeare’s Marc Antony, come to bury the ICTY, not to praise it.((Compare the more diplomatic review by Michael Karnavas.))

As I contemplated the Tribunal, I recalled that even the “closing” was illusory. I thought to myself that it was kind of like Pizza Hut (a childhood favorite of my son Jeremy), whose large sit-down restaurants have closed, but which still functions in joint locations with Taco Bell,((Completely unrelated, I then thought about Combination Pizza Hut and Taco Bell a song by Satirical Hip-Hop group Das Racist.)) with the same advertising, some of the same staff and the same uninspiring pizzas.

You see, the ICTY is not really ending, it is simply folding into a successor entity with the nondescript and non-descriptive name of Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), whose unfortunate acronym always makes me think it an ironic abbreviation of micturate. The MICT has been in place since 2010, operating in parallel to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), taking over all its functions in January 2016. Starting with a 2016 cut-off, the MICT has also begun handling trials, appeals and other matters for the ICTY. Staff, judges and prosecutors that have been wearing two hats for a few years, will now be solely under the MICT. Except for downsizing and routine turnover, many of the faces will remain the same. Indeed, the President of the MICT is a four-term president of the ICTY, who held both presidencies from 2013-2016. The Prosecutor is simply changing his letterhead. Even the building I contemplated in the snow will remain The Hague seat of the MICT for the foreseeable future.

Unfortunately, few of the mistakes of the ICTY were corrected in designing the MICT. Not surprising with so many of the same faces in planning and decision making. The one area where there had been some hope for change was in the allocation of resources for post-conviction review to address after-discovered evidence and ineffectiveness of counsel claims, and for assistance of counsel relating to conditions of incarceration for this aging population of convicted persons. While the budget for self-congratulatory activities and inapt community outreach seems likely to remain robust, the funding for investigating and developing post-conviction claims still runs the gamut from non-existent to laughably parsimonious. A disappointing, but not unexpected failure.

Stopping to take a picture of the Tribunal, one small speck of light felt positive. Just to right of the entrance-way is the office of the Association of Defense Counsel at the International Criminal Tribunals (ADC-ICT), formerly ADC-ICTY. The ADC is unique in the world of international(ized) criminal tribunals. It is not an organ of the ICTY, like the Defence Office of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, or an office of the registry, like the International Criminal Court’s Office of Public Counsel for the Defence. Instead, it is an independent entity managed and financed by its lawyer members. However, the ADC is recognized by the ICTY and MICT. Membership in the ADC is a requirement for appointment to the list of counsel at the ICTY/MICT. It is provided office space in the Tribunal, organizes internships, manages the common spaces and equipment allocated to the defense by the ICTY/MICT, and in recent years the Registrar of the Tribunal has involved the ADC in Tribunal-wide committees and projects. The Registrar also consults with the ADC on major policies affecting the work of defense teams. Though hardly a seat at the table, the formal recognition of an association of defense counsel, and a tradition of consultation, is invaluable in giving voice to the accused, through their counsel, on matters which though outside of the courtroom, affect what happens inside in many ways. The other international(ized) courts would do well to adopt this model.

As I turned from the Tribunal building to peer through the falling snow toward the rows of international flags flapping in the median, I found that I was neither inspired nor saddened by the realization that the ICTY, as such, would soon end. As a lawyer, practicing at the ICTY was an interesting experience. But in the end the ICTY is too flawed to merit the historical revision and uncritical praise it is receiving. Maybe as the baton is passed, the MICT will find a path to greater credibility and fairness, before it too rides off into the sunset. But for now, with the same people, predilections and policies, the possibility of a different result seems remote. A golden opportunity micturated away.

As I turned from the Tribunal building to peer through the falling snow toward the rows of international flags flapping in the median, I found that I was neither inspired nor saddened by the realization that the ICTY, as such, would soon end. As a lawyer, practicing at the ICTY was an interesting experience. But in the end the ICTY is too flawed to merit the historical revision and uncritical praise it is receiving. Maybe as the baton is passed, the MICT will find a path to greater credibility and fairness, before it too rides off into the sunset. But for now, with the same people, predilections and policies, the possibility of a different result seems remote. A golden opportunity micturated away.

Subsequent to the publication of this essay, the MICT changed its name to the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT). I do not presume to take credit for the name change, but …